Alien Mood

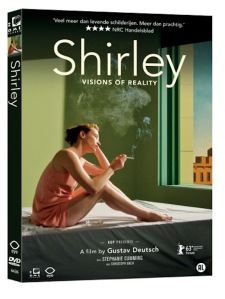

With “Shirley – Visions of Reality”, Gustav Deutsch wants to film the art of Edward Hopper while simultaneously conveying a political message. The DVD is available from 3 March. Our reviewer, Phil Butland, was intrigued but not fully convinced.

The new film from the Austrian artist Gustav Deutsch is an attempt to tell the story of a woman and her time in 13 paintings. Each scene takes place on 28 August in a year between 1931 and 1965. Each of the six to seven minute scenes contains one moment exactly reproducing a painting by the US American painter Edward Hopper. The director has said that he is doing this to show “what happened shortly before and shortly after the moment in which Hopper’s painting is frozen.”

The new film from the Austrian artist Gustav Deutsch is an attempt to tell the story of a woman and her time in 13 paintings. Each scene takes place on 28 August in a year between 1931 and 1965. Each of the six to seven minute scenes contains one moment exactly reproducing a painting by the US American painter Edward Hopper. The director has said that he is doing this to show “what happened shortly before and shortly after the moment in which Hopper’s painting is frozen.”

Chronicler of Loneliness

For this “exhibition project”, as Deutsch calls it, Hopper is perhaps more appropriate than any other painter. In more than 30 years of his work, he hardly changed his style – many of the pictures reproduced in the film show a similar room with window, sunlight and shadows. Throughout his life, Hopper worked with the same model – his wife Josephine Nivison – who ages with the paintings. In “Shirley”, Nivison is played by the Canadian dancer Stephanie Cumming.

It is not just Hopper’s style that made him predestined for such a project. More than any of his contemporaries, Hopper was able to depict the alienation and loneliness of the period between the Great Depression and the post-war era. In her recent book, the art critic Olivia Laing wrote of Hopper: “his central theme, his scenes of men and women in deserted cafes, offices and hotel lobbies remain signature images of urban isolation. Hopper’s people are often alone, or in fraught, uncommunicative groupings of twos and threes, fastened into poses that seem indicative of distress.”

In the film there are scenes with more than one person, but they rarely talk to each other. Sometimes they share a silent cigarette. Sometimes they look out of the window or sit next to each other, while we hear the woman’s internal monologue. More often the woman sits – or lies, or stands – alone in the room as we listen to her thoughts.

Each scene takes place in the year in which the displayed picture was painted. At the beginning of each scene we hear a radio broadcast of contemporary news – sometimes important, sometimes trivial. So, in 1939 we hear of the threat of a German invasion of Poland and the New York heatwave, in 1957 of the intimidation campaign against “niggers” (the term used by the radio reporter) who wanted to send their children to “white schools” and of the premiere of the film “3.10 to Yuma.”

Film as experiment

Somewhere in the film we can see the story of the actress Shirley who “never just saw the reality of the Depression years of the World War, the McCarthy era, racial conflict and the civil rights movements as an unchangeable fact, but as manufactured and something that could be changed. A woman, who as an actress is aware of the staging of reality, and with the presentation of truth, who does not see her future and identification in her own career as a start, but as a member of a collective social efficacy of theatre.”

This description comes from the film’s press release, and, to be honest, is not always easy to find in the film. The narrative structure is too opaque to follow the film this clearly. This isn’t necessarily bad – as a work of art, the film also works without such a clearly told story.

It is quite possible that Deutsch has overextended himself in presenting “Shirley” as an explicitly political film. For example, he chose 28 August as the date of each scene because Martin Luther King’s ‘March on Washington’ took place on this day in 1963 – presumably to the disgust of the racist Hopper. Similarly, the self-confident and emancipated Shirley is quite different to Nivison, who on Hopper’s request gave up her career as an artist. One year after her husband died, she killed herself. You can read all this in accompanying literature – it’s harder to find in the film.

As a political manifesto, “Shirley” is an honourable failure, but its charm lies elsewhere. Rather than telling us a story, the film washes over us visually. In particular, the use of Hopper’s colour and light compositions instils an alien mood, somewhere between cartoon and documentary.

Is ‘Shirley’ a good film? That question isn’t so easy to answer. It is unquestionably a beautiful and an interesting film. “Of course it is an experiment. I’ve never seem a film like it and I’m looking forward to seeing it.” This is how Deutsch described his motivation in directing ‘Shirley’. If you’re in the right mood, it’s definitely worthwhile to spend 90 minutes of you time with this film. You definitely won’t see anything like it anywhere else.