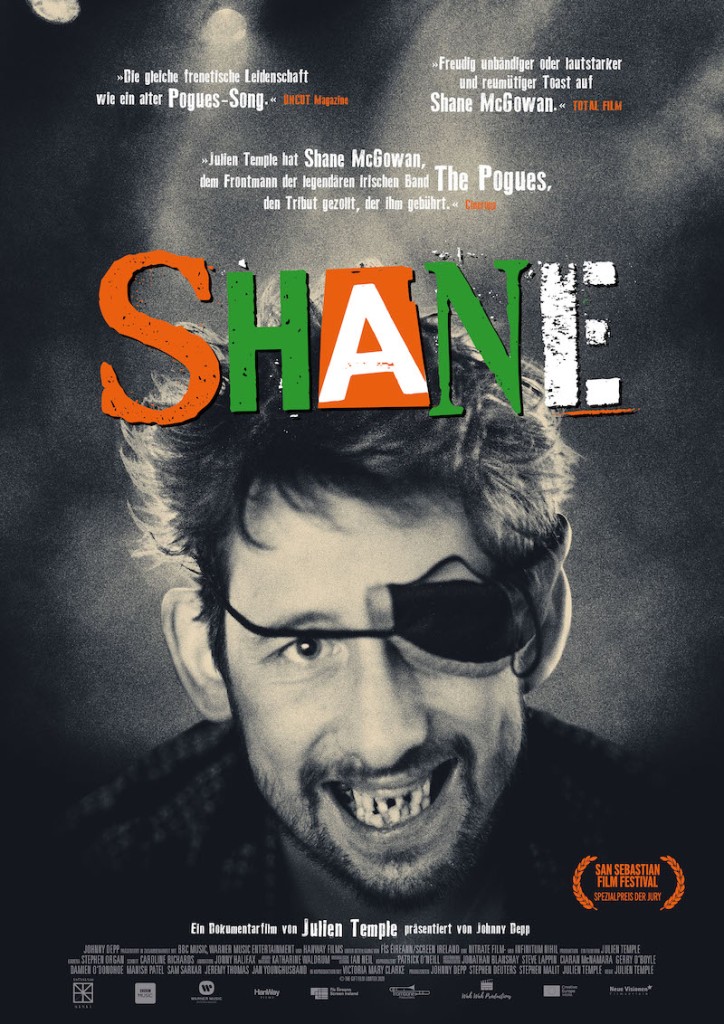

Shall we get the bad bits out of the way first? This is Un Film de Julien Temple, the posho fraud who got lucky by hanging out with the cool kids and thought it made him one of them. As usual, he directs like a hyperactive child who’s consumed too many e numbers. We are thrown endless scenes from old films which draw attention to themselves, although few actually help us to understand or appreciate the story we are being told.

And then there are the celebrity interviewers. Rather than answering questions by anyone who may have something insightful to say, MacGowan is questioned by Johnny Depp, to whose obsequious questions he offers bland catechisms, and Bobby Gillespie who he largely ignores. There are also questions from his wife, who’s not one to ask anything awkward or interesting.

Ok, now that’s out of the way, this is not a story which can be ruined by an indulgent director. Added to this, some of the interviewers do turn out to be perceptive. Take Gerry Adams (“you may remember me from the 1980s”), who shows an intelligent understanding of both Irish history and popular culture – at one stage, he bursts into a blast of the Beatles’ Blackbird.

But most interesting are Shane’s family. I could have done with much more from his dad Maurice, a friendly looking bloke with white hair and beard who is a socialist and a republican, who was kind of happy when his son got kicked out of the prestigious Westminster school, for which he’d won a scholarship. Maurice and Shane were like brothers, till Shane turned 12 and started to go off the rails.

And then there’s his sister Siobhan, who just seems so … normal. We hear a lot from her about Shane’s wild years, which were controlled by him finding punk at just the right time, of the first time she was at a concert and heard fans shouting out his name, of the time when she had to commit him to a mental hospital and everything since. She’s level headed, funny. Everything that Shane was in the early interviews that we see, but is less so now.

You see time hasn’t been good to Shane. He has the look of someone who’s permanently pissed, and talks with a slur that makes him sound a little backwards, even when he’s eloquently talking about politics or Irish literature (Yeats was always just a Western Englishman, but Shane sees much of himself in Brendan Behan, the unpleasant Republican drunkard).

There is much talk of Irishness, and although Temple is too much of a hagiographer to question Shane’s mythologising, some interesting facts peek through. So after a little too many pictures of rosy-cheeked Oirish families as Shane tells us of lacking electricity or an inside toilet, we hear in passing that he left Ireland for good at the age of 6 for … Tunbridge Wells.

At the same time, life for the Anglo-Irish wasn’t great, even at an élite public school. The mainland bombing campaign was on, and Shane was an unapologetic supporter of the IRA. Alongside the needless whimsy, we do hear what motivated him – Adams explains why it’s wrong to describe what happened in the 1840s as a famine as Ireland was exporting food throughout.

Once we get into the punk years things start to get much more exciting. Well before the Pogues, Shane became a music press celebrity after a mutual ear chewing incident with a girlfriend at a Clash concert (she upped the ante by hitting him on the head with a beer bottle). He then found fame, first as a fanzine writer, and then as the singer of one of the most exciting bands of the era.

The Pogues were exciting for 3 albums, culminating in their Hit Single, Fairytale of New York. Following this, their manager worked them to death, booking pretty much a concert a day for a year. Shane had always drank a lot (since he was 5 or 6, he claims), but the combination of drink, drugs and simply not enjoying himself did for both him and his creative energy.

It seems that the final scenes, from a concert for Shane’s 60th birthday, are supposed to show a sort of Redemption (a word that he, steeped in Catholicism, uses often). First we see Bono, with Johnny Depp on guitar behind him, singing A Rainy Night in Soho, wringing from it every last drop of the rebelliousness and vitality that made it Any Good. Then Shane is literally wheeled on – in a wheelchair – to duet with Nick Cave.

The pair sing Summer in Siam. Anyone following the film will know that this song came from the period when the Pogues drifted from their London-Irish roots and started making anything that might be a hit. Shane has already told us that this was the point that they’d turned into everything they hated. Truly, a sad end.

That Shane ends up inarticulate in a corner, being serenaded by Bono, or singing the songs that he thought robbed him of his authenticity is tragic. Temple, always keen to flatter his celebrity subjects, seems to miss this somewhat, but if we look through the directorial smoke and mirrors we see memories of a truly great time. We should celebrate Shane, and all his fellow Pogues, for everything they gave us in the early 1980s. We may never see their like again.