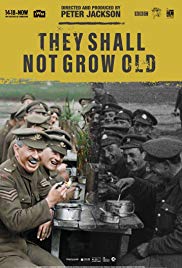

From the off, this is a technically brilliant and groundbreaking film. Just in case you missed the tales of awe when it was released, it’s a collaboration between colourisers and lip readers to reproduce home videos of world war 1 soldiers, as if they were taken last week. To this is added intensive use of interviews with veterans of that war taken from the BBC archives.

From the off, this is a technically brilliant and groundbreaking film. Just in case you missed the tales of awe when it was released, it’s a collaboration between colourisers and lip readers to reproduce home videos of world war 1 soldiers, as if they were taken last week. To this is added intensive use of interviews with veterans of that war taken from the BBC archives.

So while we hear of the initial clamour for war, the horror of the trenches, the brutal slaughter and the war that just fizzled out, mourned by no-one, these eye witness narratives are accompanied by films which approximate what the scenes being depicted actually looked like. It is, as said, a huge technical achievement.

Yet the impressiveness of what we are seeing is accompanied by an increasing feeling that we are being lied to, or at the very least manipulated. In the final 10 minutes, every single interviewee is adamant that the whole adventure was a waste of time and, to quote the great war poet Boy George, war, war is stupid. And yet the film begins with a similar unanimity – but this time it’s of people saying how the experience of war improved them as a person and gave their life purpose.

This cannot be simply explained by the change of attitude of soldiers as the war plodded on. The interviews were not taken at different phases of the war, but after it was all over. It is difficult to escape the conclusion that director Peter Jackson is cherry picking the interviews, and only playing those that fit the mood he is trying to set at that particular point in the film.

This is not an isolated incident. Towards the end if the film we hear some very moving testament about the difficulties of returning from war, and being unable to find anyone who is able to appreciate the horror of what the soldiers actually experienced. Yet only an hour before, the film is regaling us with tales of insanitory toilet conditions and visiting prostitutes in the voice of someone showing slides from his recent holiday. In fact one veteran explicitly compares the experience to a camping trip.

As the war draws to en end, and German Prisoners Of War are taken, everyone is insistent in saying that they’re “just like us”. Yet earlier on, the only reason given for the necessity of fighting was the beastly behaviour of the Germans, all Germans (one person makes the caveat that some of the Bavarians could almost have been half-Englsh, then goes on to insist the the Prussians are bastards to a man).

None of this is to say that any of the statements are inauthentic, but as soon as we realise that Jackson is picking and choosing the statements to fit his agenda, the whole illusion that these people are representative of the feelings of all participating soldiers (which is emphasized by every block of people being interviewed saying essentially the same thing) seems highly dubious.

One final, but not unrelated, point. Over the closing credits, we hear “Mademoiselles from Armentieres”, a First World War song which contains the following couplet:

“The officers get all the steaks

While all we get is belly ache”

This anger at the different experiences between officers and “ordinary” soldiers is entirely missing from the rest of the film. Instead we have posh and regional accents interspersed as if we really were all in it together.

What is lacking is the insight of films like All Quiet on the Western Front, or even the searing documentary Blackadder Goes Forth. Without this, the war is seen as something inevitable that just happened somehow, and for all the platitudes at the end about bever wanting to repeat the horrors, the people who let it happen (and indeed profited from the carnage) are let of the hook

Which is a great shame, as the gifted technicians who made the film what it is deserve better than that.